9 FAMOUS FEMALE VETERANS WHO NOT ONLY SERVED, BUT MADE HISTORY

COMMENT

SHARE

When people tell tales of military victories, derring-do, and innovation, the stories generally focus on courageous and groundbreaking men. While the US military has certainly included more than its fair share of such men over the centuries, theirs are not the only narratives worthy of praise and repetition. There is a sisterhood of bold and brave female Veterans who not only served America with dedication and valor but, in many instances, helped shape the course of history. Here are but a handful of the scores of brave women who put their lives on the line for the United States and its ideals by serving with our nation’s armed forces.

9 Famous Female Veterans That Cemented Their Place in History

Below, we're paying tribute to nine remarkable women who made history, challenged the status quo, and made significant contributions during their military and civilian careers.

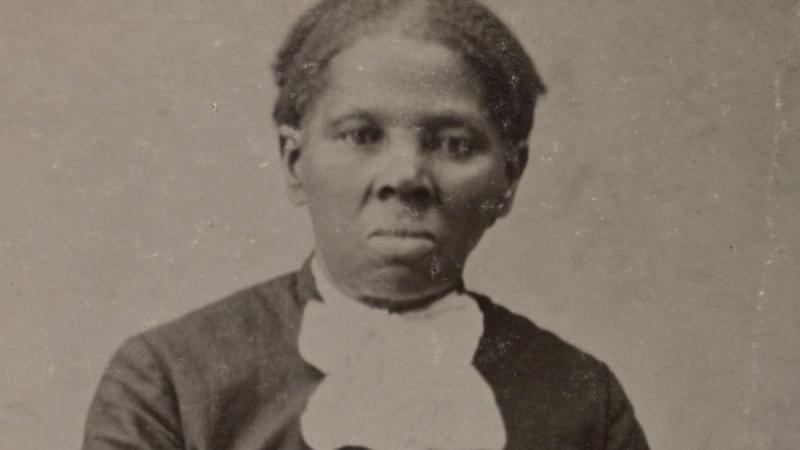

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman is probably best remembered for her legendary work as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, helping ferry and direct escaped slaves to reach freedom in the northern United States and Canada. But, as if that wasn’t impressive enough, she earned several military laurels as well.

Born a slave in Maryland in 1822, she escaped to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1849, an unimaginably courageous feat given the harsh and often fatal punishments inflicted on recaptured slaves at the time. Her flight to freedom was likely fueled by, among other things, a particularly harrowing incident in 1835 when the teenage Tubman saw firsthand a slaveowner’s attempt to recapture an escaping slave. An incident during which said slaveowner hurled a heavy object in the direction of his human quarry that missed the mark and struck Harriet instead, nearly killing her and leaving her with a lifetime of chronic headaches and occasional seizures.

After fleeing her owners, Tubman spent the next ten years making perilous journeys back to the south in order to help others held in bondage flee northwards. Over the course of thirteen arduous treks over the Mason-Dixon Line (the geographical boundary separating states where slavery was legal and those that were on the right and moral side of history) and back again, Tubman successfully freed an estimated 70 people, including her husband and parents.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Harriet enlisted in the Union Army as a nurse (not a uniformed role, but still in the service of the Army). But as the war dragged on, she took on a role that put her well-honed skills of getting through hostile territory undetected to better use: scout and spy. And on June 2nd of 1863, she personally led 150 African American Soldiers of the 2nd South Carolina Colored Infantry Regiment in a raid on the Combahee River that liberated over 700 enslaved persons. Perhaps most notably (aside from the number of human beings it brought to freedom), it was the first time in history that a woman of any race led a US military operation. And the reason that, in June of 2021, the Army honorarily inducted her into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

After the war, she founded an institute to care for elderly and infirm individuals, which she spent the rest of her life operating, and became a leading figure in the movement advocating women’s suffrage as well. She passed away in 1913 at the age of 91 and received full military honors at her funeral.

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper

Every one of the women on this list did something that impacted America, the world, and military history in some way or another. But literally every single piece of technology most humans rely on for the most basic to the most complex tasks owes its existence in some part to the work of Admiral Grace Hopper.

Born on December 9th, 1906, in New York City, Hopper was something of a prodigy, earning a master’s degree and a PhD in mathematics at Yale University in an era when few women progressed that far in academia. After America’s entry into World War II, she gave up her job as a math professor at Vassar College and attempted to join the Navy. At first rejected for being too old and too thin, she received a waiver and in 1943 was commissioned as an officer in the Naval Reserves and assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance Computation Project at Harvard University. Hopper was part of a team that produced and operated the Mark I, a large-scale, automatic calculator and a precursor to the first computers. She personally wrote A Manual of Operation for the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, considered the first ever computer manual.

After the war, Hopper remained in the Naval Reserves and continued her career in computers, helping create and operate, among other things, the Mark II and Mark III computers for the Navy and the UNIVAC I, the world’s first commercially produced computer. She was one of the first people to propose the use of English words to program computers, the idea behind most modern systems of coding, further cementing her status as a true pioneer of computing. And through the years of her groundbreaking career, she remained an officer in the Reserves.

After initially retiring in 1966 with the rank of commander, the Navy recalled her to service the following year and appointed her to the Chief of Naval Operations’ staff as Director of the Navy Programming Languages Group, where she led the effort to standardize coding across all the service’s computers. She continued serving her country in uniform until 1986, when she retired for the second (and final) time at age 79 with the rank of rear admiral. Upon her death in 1992, she received a full military burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Colonel Eileen Collins

While all the women in this article did amazing, courageous things, Colonel Collins’s accomplishments are above and beyond. Literally: she was the first woman to fly and later command a space shuttle. Born on November 19th, 1956, Collins joined the US Air Force after completing a degree in Mathematics at Syracuse University in 1978. During her early pilot training at Vance Air Force Base, members of the then-newest group of NASA astronauts underwent their parachute training there. Among the 35 people selected for the 1978 Astronaut Class (also called NASA Astronaut Group 8) were, for the very first time, African Americans, an Asian American, and a Jewish American. And six of them were women, including Sally Ride, who in 1983 became the third woman and first American woman in space.

Inspired by the proximity of women training to go to space, Collins decided to follow in their footsteps. In 1979, she became the Air Force’s first female flight instructor and spent the next 11 years flying and teaching others to fly various training jets and C-141 Starlifters. By January of 1990, she reached the rank of colonel, earned two master’s degrees, and received the news she’d been hoping for since 1978: NASA selected her for Astronaut Group 13, the first American woman ever selected to soar into space as a pilot.

After several years of additional training, Colonel Collins finally made it to space on February 3rd, 1995, when shuttle Discovery blasted off with her at the stick. Over the course of the mission, STS-36, she and the rest of the crew spent over 8 days at an altitude of 213 nautical miles, travelling three million miles as they orbited the Earth. She returned to space as a pilot for STS-84 in May 1997. And on July 3rd, 1999, Collins made history as the first woman to command a space shuttle when the Columbia took off for STS-93, a mission that included the delivery of the heaviest payload ever deployed via shuttle: the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

She commanded a shuttle again during the STS-114 mission in July-August 2005, the first shuttle mission carried out by NASA since the tragic loss of the Columbia on February 1st, 2003. When asked beforehand if she was worried about flying on the shuttle again after the Columbia disaster, she made it clear she was not. Having already retired from the Air Force in January of 2005, she left NASA in 2006, having spent nearly thirty years in service to her country, including over 6,751 hours in 30 different types of aircraft and 872 hours in space.

Private Sarah Emma Edmonds

When, in mid-April of 1863, the men of the 2nd Michigan Infantry found out their comrade, Private Franklin Thompson, had deserted, some were no doubt surprised. After all, the boyish young man was not only suffering badly from malaria but had bravely fought by their sides in some of the most brutal and bloody battles of the Civil War. What could lead an experienced fighter to commit the soldier’s ultimate sin? The answer is, as with many deserters, fear.

But Private Thompson did not fear further combat; he feared that medical care for his illness would reveal his (or, rather, her) true identity: Sarah Emma Edmonds. Born in New Brunswick, Canada, in 1841, Sarah fled her hometown in 1957 to escape an abusive father who planned to marry her off against her will. Knowing how difficult it was for a single woman to travel and find work at the time, she disguised herself as a man and adopted the persona of Franklin Thompson. She soon found work as a travelling bible salesman, but in the spring of 1861, while waiting at a train station in Flint, Michigan, she heard someone read out Lincoln’s call for volunteers.

Answering Lincoln’s call, Edmonds (as Thompson) joined the 2nd Michigan as a field nurse with the rank of private. For the next two years, she served on multiple battlefields, including the Siege of Yorktown and the Battle of Second Manassas (during which a mule threw her, resulting in a broken leg), tending to the wounded under fire, carrying stretchers, and occasionally picking up a weapon to fire at the enemy. She also worked as a mail carrier, carrying vital military correspondence across miles and miles of dangerous enemy territory. She later claimed that during this time she repeatedly worked as a spy, gathering information while in disguise behind enemy lines. Her claims remain unproven, but her courage under fire during her time as a soldier is undisputed. But in 1863, while her unit was stationed in Kentucky, she fell seriously ill with malaria and made the difficult decision to run away rather than be sent to a military hospital. Franklin Thompson was labeled a deserter.

After recovering from her illness, Edmonds rejoined the war effort as herself. In June of 1863, she joined the United States Christian Commission as a nurse and spent the remainder of the war tending to the wounded. In 1864, she published her memoir (which is the source of those disputed spy claims and several others historians remain unsure of, like her purported service at the Battle of Antietam), Unsexed, or the Female Soldier, though only after it was reissued as Nurse and Spy in the Union Army the following year did it become a bestseller.

She went on to marry a carpenter named Linus Seelye in 1867 and, in 1876, attended a reunion of the 2nd Michigan to the surprise of her former comrades. But they seemingly accepted her as one of their own, as their support resulted in Congress formally recognizing Edmonds as a Veteran of the regiment and awarding her a military pension in 1884. And in 1897, a few years before she passed away at the age of 56, she became one of those three women accepted into the Grand Army of the Republic (keep reading to find out who the third one was).

Kady Brownell

Kady Brownell’s life began with a battle. While observing her husband engaged in combat against a group of indigenous people of South Africa in 1842, the pregnant wife of British Army Colonel George Southwell went into labor. Taken to a tent in a nearby army camp, she gave birth to a baby girl whom Colonel Southwell named Kady after a close friend of his. The mother died soon after, and her mother first took her to England when his time in Africa ended. But he soon departed for another overseas assignment, leaving the young girl in the care of another couple who eventually took her with them when they emigrated to America. In April of 1861, Kady, then working as a weaver in Providence, Rhode Island, married Robert Brownell. Three days later, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 750,000 troops to enlist to defend the Union in the aftermath of the Battle of Fort Sumter. Robert decided to enlist. Kady did too. He succeeded in joining the 5th Rhode Island Infantry Regiment. She was forcibly sent home.

Rather than leave it at that, Kady went directly to Rhode Island Governor William Sprague, who enlisted the determined young woman as a “daughter of the regiment.” After reuniting with her husband and the unit, she was now officially a vivandière (a French term for a person, usually a woman, attached to a military formation as a merchant or canteen operator). Kady soon found herself at the front. She served under fire during the Battle of First Manassas (the first major engagement of the war) and the Battle of New Berne.

During the latter, she took on a duty beyond her usual ones: when the color bearer (the Soldier who held a unit’s flag upright in battle) of another Rhode Island regiment fell, she picked up the standard and carried it to safety despite being wounded in the process. Robert received a grievous wound of his own during the fighting and was deemed unfit for further service, resulting in both of their discharges.

While historians estimate many women served (mostly disguised as men) on both sides of the Civil War, Kady Brownell was the only one to receive formal discharge papers in her own name from the Union Army. In 1870, she became a member of the Union Army Veterans’ association, the Grand Army of the Republic, making her the first and one of only three women accepted into the organization (don’t worry, we’ll get to the other two). She began receiving a military pension (which, as will undoubtedly surprise exactly zero women who’ve ever compared their paychecks to their male coworkers’, was a wholly unacceptable 1/3rd the amount of her husband’s) in 1884 and passed away in January of 1915.

Margaret Corbin

While every single woman on this list of unfathomably impressive and brave women is worthy of the utmost admiration, this one has a special place in this writer’s heart for a single, simple reason: despite serving with different branches in different centuries, we both served the King of Battle. Born November 12th, 1851, in rural western Pennsylvania, Margaret Corbin (nee Cochran) learned of war’s tragic consequences early in her life. At age four, with the French and Indian War in its early days, her parents sent Margaret and her brother to live with an uncle who lived further from the frontier that saw so much fighting between the British, French, and the various Native American tribes allied with each side.

The decision proved prescient as mere months later, a raid by one such tribe killed her father and abducted her mother, whom Margaret never saw again. She continued to live with her uncle, who officially adopted her, until she married a Virginia-born farmer named John Corbin in 1772. For three years, the young Corbin couple worked the land of their small Pennsylvania farm. But their simple, pastoral life ended in 1775 when John enlisted in an artillery unit of the Pennsylvania militia. Rather than remain on their farm, Margaret, like many women whose husbands, fathers, and/or brothers joined up, opted to become a camp follower. These women carried out all manner of important jobs, from mending clothes to cooking for the troops to caring for the wounded and the ill. Needless to say, Margaret and her fellows provided unquestionably vital services to their units and suffered through many of the very same hardships the soldiers did.

By the summer of 1776, the Corbin couple’s artillery unit was part of the large Continental force, headed by General George Washington, defending New York City. After the redcoats drove the Americans out of nearby Long Island and Brooklyn in August, they began landing troops on the island of Manhattan on September 15th. Over the following weeks, Washington’s forces continued to fall back in the face of the British advance. On November 16th, the British launched an attack against one of the last Continental strongholds on the island of Manhattan: Fort Washington.

During the battle, John served in his usual role as loader for a cannon while Margaret, along with many of her camp followers, brought buckets of water to the front line to help cool and clean gun barrels and carry wounded men back out of harm’s way. But on one of her trips forward with the bucket, she found John and several others of his cannon crew dead. Margaret’s response to this heartbreaking sight? She dropped her bucket and joined the gun crew, helping them fire shot after shot at the advancing enemy until, grievously wounded in the chest, jaw, and left arm by musket balls and grapeshot, she fell.

After overrunning the fort, the British found the bloodied young woman and gave her what medical care they could (she would never again have use of her wounded arm) before paroling her back to the Continental Army. Initially sent to an Army hospital, she eventually wound up as a member of the Invalid Regiment, a unit of Continental veterans crippled by the war, at West Point, New York. In 1779, in recognition of her service, the Continental Congress awarded her a military pension (at a rate half the monthly rate of a male combatant, though hers also included allowances for clothing and rum), making her the first woman to receive one in American history. Additionally, General Henry Knox (the Continental Army’s Chief of Artillery and later America’s first Secretary of War) provided her a private servant to help her take care of herself. Mustered out of the Army after the war’s end in 1783, Margaret developed a reputation as a hard-drinker and heavy smoker in constant pain from her wounds.

She remained at West Point until her death seven years later at the age of 48. She was buried without military honors, and an attempt to rebury her remains with the proper respect in 1926 proved fruitless when later investigation discovered the remains weren’t actually hers. In 2011, Congress voted to rename the Manhattan VA Medical Center to the Margaret Cochran Corbin Campus of the New York Harbor Health Care System, the first VA hospital named for a woman, affording Margaret a small fraction of the recognition she deserves.

Doctor Mary Edwards Walker

The Medal of Honor, the highest honor awarded to those in military service to the United States, is given only to those who perform unbelievable acts of courage and superhuman displays of character under fire. In the decades since its establishment in 1861, fewer than 4,000 of the millions who served America in warfare have earned it. And, as of today, only one of them belongs to the same gender as the rest of those listed in this article: Doctor Mary Edwards Walker.

Born in 1832 in Oswego, New York, Walker first made history years before her military service when, in 1855, she became the second woman (after Doctor Elizabeth Blackwell) in America to graduate from medical school. After earning her degree, she worked in private practice for the next six years and gained a small degree of notoriety for her feminist attitudes and habits, such refusing to dress in typical women’s clothes of the day. During her wedding, for example, she refused to promise to “obey” her future (and soon-to-be ex) husband and wore a coat and trousers (with a skirt over them).

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, she attempted to join the Union Army as a doctor, but despite the great need for medical professionals on the battlefield, the US military would not allow a woman in the ranks. Determined to support the cause anyway, she began working as a volunteer assistant surgeon at a makeshift hospital in Washington, D.C. Her reputation as a highly skilled physician earned her increasing respect and, in late 1862, a chance to practice on the front lines. The Army agreed to take her on as a field surgeon, albeit as a volunteer without military rank. For the next year and a half, she tended the wounded and dying on both sides during and after several major clashes, including the Battle of Fredericksburg and the Battle of Chattanooga.

Her service at the front came to an unexpected end in April 1864 when, while providing medical care to wounded troops in Confederate territory (something she often did, despite her serving with the Union), southern troops took her prisoner on suspicion of being a spy. She spent the next four months at Castle Thunder, the notoriously brutal Confederate prisoner of war facility in Richmond, Virginia. Although relatively brief, during her time in those harsh conditions, she suffered from extreme malnourishment, bronchitis, and a permanent degradation of her vision. In August 1864, the Army swapped a captured Confederate surgeon for Dr. Walker. She remained in service to the United States as a doctor through the remainder of the war, but she did not return to the front lines.

On November 11th, 1865, in recognition of her courage and sacrifice, President Andrew Johnson awarded Dr. Walker the Medal of Honor, making her the only woman to receive the nation’s highest military decoration thus far. In the decades after the war, she became a leading advocate for women’s suffrage and other feminist causes, including the right to wear “men’s clothing.” Arrested multiple times for having the audacity to wear shirts, jackets, and trousers (and often a top hat as well) in public rather than dresses, she famously responded to criticism of her attire by saying, “I don't wear men's clothes, I wear my own clothes.”

In 1916, the Army began a review of several thousand Medal of Honor citations they considered questionable. They eventually decided to rescind over 900 of the medals awarded, including Dr. Walker's. Not because her actions did not merit it, but (according to the reviewers) because she was not a uniformed servicemember during the war. By contrast, General Leonard Wood, who earned his Medal of Honor while working as a civilian doctor with the Army before he joined the service, was allowed to keep his. Despite the Army’s decision, she continued to wear her medal until her death in 1919. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter undid the Army’s questionable decision and posthumously restored Dr. Walker’s Medal of Honor.

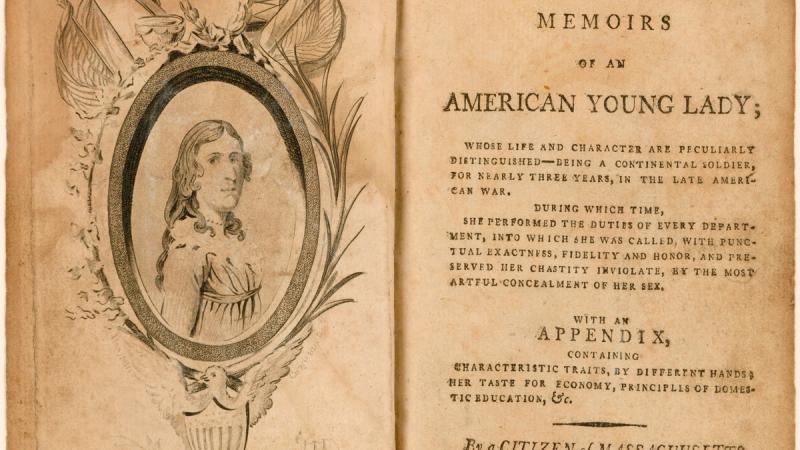

Deborah Sampson

The soldiers of the Continental Army were no strangers to disease. So, it wasn’t out of the ordinary when Robert Shurtleff (sometimes spelled Shurtliff) of the 4th Massachusetts Regiment fell ill during the summer of 1783. After all, he was one of the many soldiers afflicted by an epidemic then running rampant through the city of Philadelphia. What was out of the ordinary was that, after falling unconscious due to a high fever, the doctor who tended to the sick young man discovered he wasn’t Robert Shurtleff. He wasn’t even a young man. The suffering soldier under his care was 23-year-old Deborah Sampson, a young woman who’d spent the last year and a half fighting for the patriot cause disguised as a man.

Born in the town of Plympton, Massachusetts, in 1760, Deborah endured a rather hardscrabble youth. At the age of five, her father either ran off or died at sea (depending on the account) and left her, her mother, and her six other siblings destitute. At age 10, Deborah went into indentured servitude, bound as a servant to another family and provided with food, clothes, and housing but no pay, until the age of eighteen. After being freed, the self-educated Sampson spent the next few years making a living working as a teacher during the summer and a weaver in the winter.

But on May 23rd of 1782, this hardworking woman of modest means made the life-changing decision to join the Continental Army as Private Shurtleff, a soldier in the 4th Massachusetts’s Light Infantry. Deployed with her unit to the continuously contested Hudson Valley region of New York, Sampson spent over a year engaging in numerous skirmishes with Tory (meaning loyalist, British-aligned) militia troops, raids, and reconnaissance missions. She even claimed to have travelled south to serve under General Washington during his conclusive victory at the Battle of Yorktown, though that (unlike the other details of her courageous service) is somewhat disputed. Throughout her time in combat, she managed to keep her gender a secret at all times, even going so far as to refuse medical care after taking a pistol shot to the thigh and removing the ball herself. It wasn’t until sickness struck her while stationed in Philadelphia that her superior officers learned of her true identity.

On September 3rd, 1873, only a few weeks after Sampson fell ill, the Treaty of Paris formalized the end of the American War of Independence. Despite the fact that she’d been legally ineligible to serve and had done so under a false identity, the Continental Army understandably decided to grant Sampson an Honorable Discharge in late October. Granted a military pension by her home state, she returned to Massachusetts, where she married a farmer, gave birth to three children, and adopted a fourth.

In her later years, she published a ghostwritten memoir and gave lectures on her service in many large cities across the northeast. She also continued to petition Congress that she receive a federal pension for her service and wounds in addition to the one granted by her state, but they repeatedly refused. Deborah Sampson, who briefly lived as Robert Shurtleff, died at the age of 66 in 1827.

Brigadier General Hazel Johnson-Brown

Every single woman covered in this article struggled valiantly against, among so many other things, the scourge of sexism. But General Hazel Johnson-Brown also managed to rise through the ranks while facing unimaginable racism to boot. Born to a West Chester, Pennsylvania, farming family in 1927, Hazel grew up dreaming of a career as a nurse while working as a domestic servant to help support her parents and siblings from the age of twelve onwards.

After graduating from high school, she applied to the West Chester School of Nursing, only for it to reject her for being African-American. Undeterred, she looked for opportunities outside her home state and eventually matriculated into the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing in New York City, from which she graduated in 1950. After several years working as a nurse in Harlem, she returned to Pennsylvania and began working for a local VA hospital. Her proximity to Veterans piqued her interest in putting her skills to use on behalf of the military, and in 1955, she joined the US Army Nurse Corps.

At the end of her two-year contract, Johnson-Brown left the service and went back to the VA. But upon learning the Army was offering financial assistance to anyone with a nursing degree interested in furthering their credentials in that field by earning a bachelor’s degree, she decided to once again don the uniform. After earning her diploma in 1959, she returned to active duty. Over the next twenty years, she rose through the ranks and served in various roles and commands throughout the Nurse Corps, including a 1966 tour in Vietnam that ended prematurely after she contracted a serious lung infection. She also earned a master’s degree and a doctorate during those decades in addition to all her other duties. And in 1979, after completing a tour as the chief nurse of a hospital in Seoul, South Korea, the Army appointed Johnson-Brown Chief of the Army Nurse Corps and promoted her to the rank of brigadier general. She was the first African-American woman to achieve a flag rank in the United States military.

General Johnson-Brown retired from the Army in 1983, but that did not end her service to her profession or her country. She taught nursing at Georgetown University and George Mason University for years afterwards. And during the Persian Gulf War, she volunteered at the community hospital on Fort Belvoir, Virginia, to help the injured and wounded being treated there. Hazel Johnson-Brown’s life of service and sacrifice ended at the ripe old age of 83 in August of 2011. But her legacy as a champion for women and minorities serving in America’s armed forces continues to live on.

Celebrating and Honoring America’s Female Veterans

Though barred from formal service for most of our nation’s history, women have served with and alongside America’s armed forces since its founding. The women with lives detailed in this article are but a handful of those who risked their lives to defend the United States.

Who went up against not only the enemy, but their fellow citizens who considered them unable or undeserving of military service. They stood tall against those who opposed them and their rights on both sides of the fight. And we honor them and all their unsung sisters as heroes.

Related reads:

Join the Conversation

BY PAUL MOONEY

Veteran & Military Affairs Correspondent at VeteranLife

Marine Veteran

Paul D. Mooney is an award-winning writer, filmmaker, and former Marine Corps officer (2008–2012). He brings a unique perspective to military reporting, combining firsthand service experience with expertise in storytelling and communications. With degrees from Boston University, Sarah Lawrence Coll...

Credentials

Expertise

Paul D. Mooney is an award-winning writer, filmmaker, and former Marine Corps officer (2008–2012). He brings a unique perspective to military reporting, combining firsthand service experience with expertise in storytelling and communications. With degrees from Boston University, Sarah Lawrence Coll...